Paupers Child

Contents:

A brief note about traditional academic publishing

The boys like the girls had supper at 6. Some boys were taught engineering and plumbing as there were two steam engines on the premises. This training was designed to produce literate and numerate wives and servants, and girls from Norwood apparently found and kept places in domestic service and were generally reported as giving satisfaction to their employers.

In Swinton, the training regime required children to resist temptations and distractions. The junior playground was lined on two sides by currant bushes, and if any of the fruit was taken by children prematurely they were left out of the subsequent picking and eating of the ripe fruits. While ideologically and geographically close large urban unions in England embraced the idea of merging to form school districts, the process proved more problematic in both rural and urban Wales.

Andrew Doyle, the poor law inspector responsible for Wales and the border regions was a driving force in the establishment of separate schools for pauper children, but his arguments failed to persuade poor law unions in north Wales to create school districts. Andrew Doyle had used the Bridgnorth Union in Shropshire as a model of poor law perfection. In the s Florence Davenport Hill had accompanied her father on his philanthropic tours, and their visit to the Mettray colony in France must have stayed in her mind when she wrote Children of the State , in which she claimed that large numbers in district schools could be overcome by dividing into smaller groups such as at Mettray.

He left for work with the boys every morning, returned home for midday meal and went back to work for the afternoon. They ate meals together in their cottage which were prepared by their matron and the older girls, prayers were said, chores were done and suitable leisure pursuits were encouraged. However, the system included very large self-contained establishments almost resembling a small town with schools, workshops and hospitals on the enclosed site. In some establishments the children appeared to be isolated within these large cottage homes.

Letitia Lloyd began her employment at Swansea cottage homes in the mids and died there in at the age of 68, she was praised for her vigilance and kindness during a measles outbreak, and other periods of sickness at the home. Like the district schools these establishments were expensive: These large homes were rejected by unions in south Wales which nevertheless took the lead in establishing smaller cottage homes, first in Swansea in , and in the Bryncoch Cottage Homes in Neath which housed 44 children in groups of 20 and The Welsh unions, although criticised at times for their espousal of smaller, cheaper homes and therefore less well endowed with integral facilities, avoided some of the isolation experienced by other schools because of the integration of their children into the local community.

Similarly their more manageable size meant that local philanthropists could indulge the entire establishment in special teas, outings and innumerable Christmas events. He also suggested more books and some pictures for the walls, although he commended the policy of sending the best scholars to the county school, which implies that education came before homeliness. Many children came back to visit these places they thought of as home. Former pupils who had returned for a visit to Norwood were given dinner and tea. Some children however resisted discipline by unruly behaviour or running away.

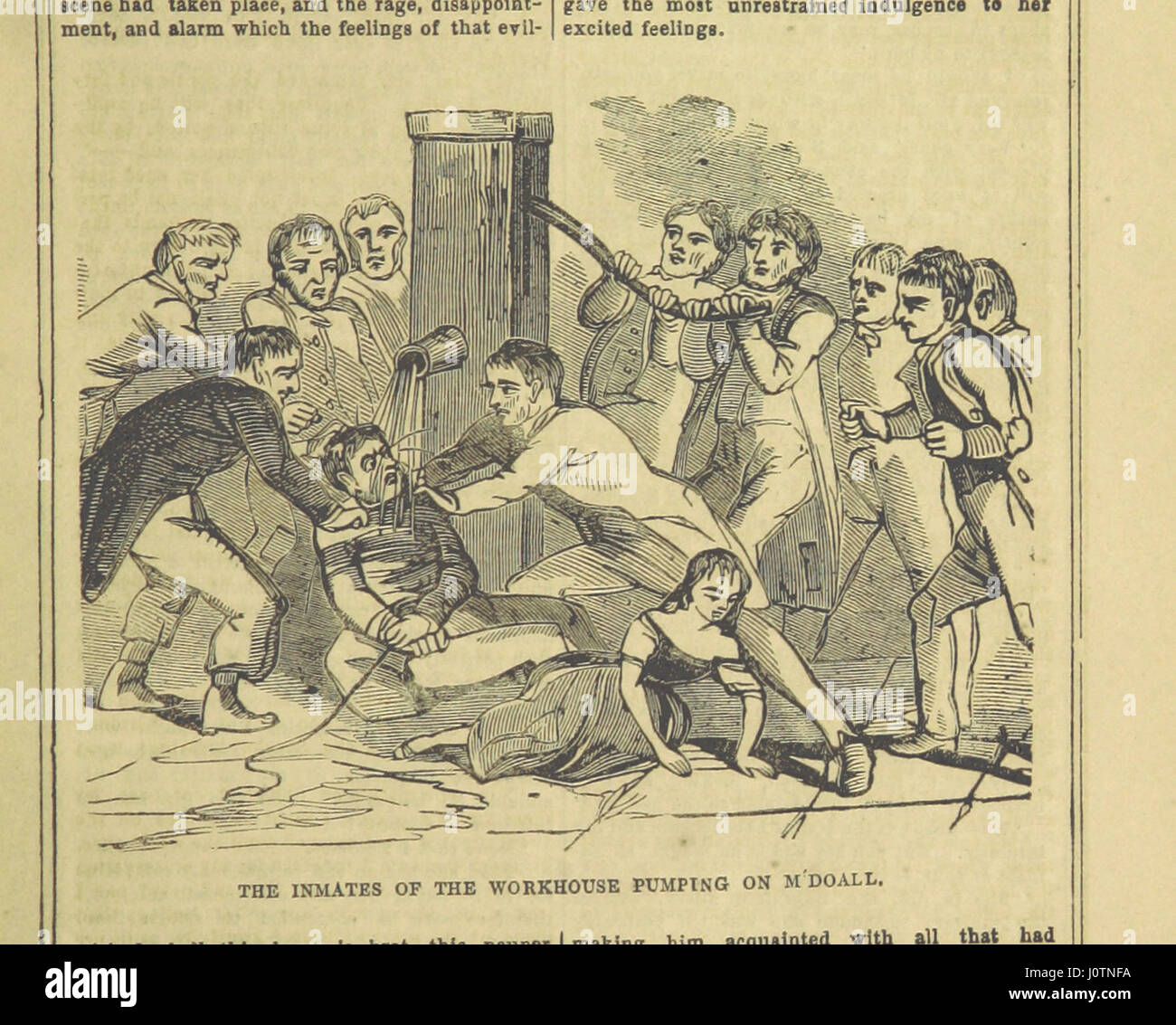

Howard recalled that the boys took part in at least one organised fight a week, generally on Fridays after school. Across England and Wales a multiplicity of strategies to remove children from workhouses was evident. Ins and outs were children who were removed and then brought back to poor law establishments by their parents, often on a regular basis.

In Shoreditch, the clerk to the guardians reported that in one year, 52 children who had passed through the cottage homes were regarded as ins and outs. Florence Davenport Hill was unequivocal in her condemnation: Children would be looked after in groups of up to 20 in ordinary houses scattered about the union and would live as a family with a house mother and attend local schools. The latter was assumed to be brought back from local schools, where standards were not as particular as those of poor law inspectors. Presumably, the children also learned valuable life lessons about budgeting and hygiene from their far from perfect house mothers.

As with all these strategies to remove children from the workhouse, the staff were pivotal to the success or failure of the scattered homes. Inspections did not prevent children being seriously beaten in Plymouth, as well as locked in coal houses and kept under water in the bath, by one house mother. Not all staff were remembered for their cruelty. As workhouse boy himself Benbow had been injured while rescuing someone from a fire.

Luck played a huge part in the wellbeing of these children who could be billeted with a kindly, neglectful or cruel carer. Poor law regulations intended to give the children education and training to fit them for work and parenthood, although how many really overcame the stigma of the poor law child even away from the workhouse? When I was fourteen, it was when scoring for the Hanwell team one Saturday afternoon at an away game, that I first became conscious of my lowly status in Society.

And being a highly sensitive lad, I was never to forget the incident which I will not disclose here which occurred that afternoon. The shock of the realization of being in what that I was considered to be a member of the lowest form of human creation, was an experience from which I have never fully recovered. It affected the nerves and my whole outlook upon life. It affected my confidence and personality and it left a feeling of a deep and profound inferiority complex which generally has overshadowed everything I have tried to accomplish over the years.

In an article, Charles Dickens had championed the boarding-out system which placed pauper children in the homes of paid foster parents. Furthermore, discussions supporting boarding-out were especially charged with sentimentality and often idealised foster parents, foster homes particularly rural homes and fostered children.

Subsequently, during the s and s the Poor Law Board came under persistent pressure from local poor law unions and child welfare campaigners to support boarding-out. Florence Davenport Hill was one of over 3, women to sign a petition in favour of boarding-out which was presented to George Goschen, the new president of the Poor Law Board, in For many metropolitan and densely populated unions, a policy of boarding-out pauper children in the overcrowded, anonymous and what was perceived as undomesticated homes of their urban poor was anathema.

The actions of their guardians both encapsulate what poor law inspectors feared most about boarding-out, and in particular shows how important regional research is to know the bigger picture of strategies such as boarding-out.

Although many ideological and practical variances differentiate boarding-out from modern foster care, the main difficulty of a shortfall of suitable foster parents remains the same. However, historical retrospectives of foster care written by child policy specialists offer more information, but tend to perceive boarding-out as the under-developed origins of an enlightened system.

In one of two articles devoted to boarding-out, Michael Horsburgh, using comprehensive primary research, foregrounds the discussions and campaigns of the poor law authorities and child welfare activists and also offers useful insights into the roles of women and class within the boarding-out debates. To the Poor Law Board, paying such an allowance signified unauthorised and unfettered out-relief. It also sidestepped principles of less eligibility, as independent labourers were unable to pay for their own children to be placed in situations.

The argument that farmed-out pauper children were thus advantaged compared with non-pauper children had been used successfully to end the practice in Penrith union in The youngest, Mary Ann Stephens, was ten and the others between the ages of eleven to thirteen. The boys were slightly older; David Rosser was fourteen and the others thirteen.

None of the children appear to have attended school, but all were recorded as being able to read and write, and all save David Rosser attended Sunday School regularly. Just four years later, in , the policy came under fire again from both H. Schools Inspectorate and the Poor Law Board. At a meeting following the review, most guardians did not seem to question the apparent good health and treatment of the children, even though it had been discovered that some of the children wore borrowed clothes to the review.

One guardian thought that there was not a farmer in the country who would treat pauper children any different from his own. In addition to the eighteen pence or two shillings weekly given to farmers for the maintenance of the children, Swansea Union also paid for the education of many of the farmed-out children. The guardians were particularly disconcerted to discover that one girl had never been sent to school, nor had she ever attended a church or chapel.

The committee discovered that the elder two of the four children currently farmed out to Solomon Francis, a farmer in Llangyfelach, could neither read nor write, and consequently was dismayed to learn that Francis had brought up 21 pauper children from infancy. Consequently, although education was perceived as vital for the future independence of a child, many guardians repeatedly rejected their present workhouse as an appropriate locus for their pauper children.

As with objections in earlier years, the Board also thought that the employment of non-pauper children would be disadvantaged as the poor law assisted children would be seen as cheaper labour. It is unclear again whether, on this occasion, unions acted against the wishes of the central authorities.

The Pauper Children (Ireland) Act (2 Edw. VII c. 16) was an Act of Parliament of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, given the royal assent on 22 July. Pauper definition is - a person destitute of means except such as are derived from charity; How to use pauper in a sentence. Kids Definition of pauper.

The Poor Law Board was subjected to persistent pressure by Boards of Guardians and child welfare campaigners to endorse boarding-out for pauper children at this time. Barnardo felt that the boarding-out system was superior to either barrack schools or cottage homes. Doyle also articulated his concern about the moral welfare of the children, in particular the sleeping arrangements within foster homes. In a two-roomed house he was disconcerted to find a lodger occupying one room and the child sleeping with the foster-parents in the other. This apparent neglect of the monitoring of foster parents caused Swansea Union to be condemned by the national press and child welfare campaigners to the extent that they were used as an illustration of how the boarding-out system could fail.

Was the Swansea Union neglectful of their boarded out children as Doyle and previous inspectors alleged?

- Alejandra! Or Morning Dews!;

- Children & Cotton - Learning Zone for Social Studies & Citizenship.

- .

- Hard Drive! As the Disc Turns.

- Urban Shaman;

- Suma y narracion de los Incas, que los indios llamaron Capaccuna, que fueron señores de la ciudad de.

- Pauper Children (Ireland) Act - Wikipedia.

Similarly, Harriett P lived with her grandmother who was a kind and affectionate woman, but her house was described as filthy and untidy. Swansea Union apparently intended to supervise the children they placed with foster parents. It was recorded in that each boarded out child was to be seen at least once a month by the local relieving officer. The report written by Messrs.

However, one guardian M. Williams felt the boarding out system as a whole was unsatisfactory and a separate school would offer better facilities for the children. For both Llewelyns, signifiers of poverty such as overcrowding and dirt did not necessarily equate to neglect or mistreatment. There are enough of bruised affections in the world; enough of misery; enough of broken hearts, and I should not like to be the agent of adding another drop in the ocean. These words, spoken by John Dillwyn Llewelyn, reflect again how well-intentioned guardians mitigated the worst effects of poor law policy.

He appears to have visited the majority of boarded out children over a very wide area in , and his subsequent report is a fusion of care, sentimentality and recognition of the living conditions of the poor. In his own village of Penllegare, the children were apparently visited regularly by his own family; Catherine Murphy, Mary Price, Emily Popham and Catherine Reeves were all boarded out in the village with different families and all were reported as being safe and doing well. He also visited three children living with their aunt whom Doyle had singled out for criticism.

One child, David Howell, was painfully thin, spitting blood and thought likely to die. The children were boarded out with Mrs Morris and her collier husband. Most of these children lived with relatives grandmothers, aunts, brothers or sisters, and Dillwyn Llewelyn appeared to believe that family ties were important to their wellbeing and future independence; this contradicts to some extent his previous statement that isolated rural areas separated children from their former vicious companions.

It appears that many of the children mentioned by Dillwyn Llewelyn lived with their relatives who were paid around one shilling and sixpence to two shillings a week. Benjamin and Joseph Levi, nine and seven year old orphans, were boarded out together as were seven and five year old Margaret and Thomas Park, along with several others. Dillwyn Llewelyn also related the circumstances of two children who were not living with relatives, but who had been informally adopted by their foster parents.

Dillwyn Llewelyn remarked particularly that John Whelan who lived in Pontardulais could write his name. Of course, not all children were happy. Mary Ann Evans chose to run away from her foster parents in Plasmarl back to the workhouse. In her speech, Mason had claimed particularly that children should never be boarded out unless they could be supervised by a ladies committee. It does appear that following the criticism and resultant publicity of the s that Swansea Union embarked upon a more regulated regime for the protection of their boarded out children.

Across England and Wales, boarding-out was becoming an increasingly popular strategy and the number of children being boarded out doubled between and Rural homes continued to be imagined as the normal place for boarded out children. Mason also recounted how a farmer had been imprisoned for cruelty against a four year old girl. She was to be a trained nurse between the ages of 25 and 40 and preferably a Welsh speaker.

This was more than the relieving officers received and only slightly less than the Union Clerk. Swansea Union appear to have boarded out pauper children throughout the period, both with and without the cooperation or indeed knowledge of the central authorities. Although the system was imagined as providing a normal family life for pauper children, it also demanded a high level of supervision to satisfy the central authorities.

Many of the children who were boarded out were placed in the homes of relatives and the impact of these relationships was not always perceived as positive. Although parents and children living together as a unit represented an imagined normality in middle-class and respectable working-class families, when this unit required poor law financial support in order to stay in the home, imaginings were considerably more slippery and contentious. In Swansea, the figure was eleven to one and between and the average number of children relieved in the workhouse was 63, while children received outdoor relief.

Indeed, the inability of fractured families to conform to what was imagined as normal appears to be a major factor for outdoor relief generating such widespread anxiety. Historical scholarship regarding these thousands of outdoor pauper children is a neglected area. Similarly, both legislative and personal testimony, not related directly to outdoor relief, offer us glimpses into the practice of outdoor relief and the lives of outdoor paupers, as well as the poor in general.

This chapter unpicks these diverse sources to expose a more rounded interpretation of outdoor relief than is often attempted. Analysis will extend to the ways in which outdoor relief was perceived by regional unions, the central authorities and the often contradictory and autonomous practice of outdoor relief.

For most of the period , the education of outdoor pauper children persisted as a site of contention. As discussed in previous chapters, education was perceived as a primary means of removing inbred pauperism from a child and this chapter will question the involvement of poor law unions, the central authorities and also the significance of parental engagement in the education of outdoor pauper children. The lived experiences of the tens of thousands of outdoor pauper children remain largely unrevealed by poor law sources.

However, this chapter sheds light on the lives of these hidden children via a close reading of reports, autobiographies and newspapers in order to contextualise experiences of poverty and thus offer representations of the lives and expectations of outdoor pauper children. It has proved problematic to determine any consistent pattern relating to the granting of outdoor relief.

The apparent contradictory nature of decisions recorded in the minutes books may be the result of incomplete clarification within the records. The case of Rebecca Bonsey in is markedly illustrative of these inconsistencies. Bonsey and her seven children had been deserted by her husband. However, on the same day, and the very next entry in the minute book, the guardians allowed Gwenllian Lewis, again deserted by her husband, outdoor relief of four shillings a week for four weeks.

It appears that poor laws inspectors also experienced this difficulty and is demonstrated by a very long report by Andrew Doyle which resonates with palpable frustration. One of his criticisms was the lack of information recorded by relieving officers concerning the circumstances of applicants for outdoor relief. The chairs of this committee tended to change constantly which, as Doyle illustrated, resulted in decisions being reversed from meeting to meeting. Although only one of many examples recorded by Doyle, the case of Ann Strawbridge and her two children, aged 10 and 8, illustrates his argument particularly well.

Strawbridge had been deserted by her husband and her relief was left to the discretion of the relieving officer for one week. The relieving officer subsequently located an older son of 17 who was earning 13 shillings a week. When she came before the guardians again, the relieving officer recommended an offer of the workhouse. Instead, a different chairman allowed her three shillings for one week and a fortnight later, a different chairman again awarded her three shillings every week. Outdoor relief was to be denied to deserted wives during the first year of desertion.

Wives and families of convicted prisoners, soldiers, sailors or militiamen on duty, able bodied widows with one child over two years old, and single women with illegitimate children. There appears to be more controversy surrounding the outdoor relief of deserted wives than of widows, and is perhaps indicative of an imagined model of respectability. Widows, in this context, signified a blameless fracturing of the family unit, while deserted wives could be perceived as tainted by association with their perfidious husbands.

This compares with 50 deserted wives and 94 dependent children who were allowed outdoor relief. This situation was perceived to be magnified considerably for outdoor pauper children. In , Jelinger Symons had condemned the lack of educational provision for outdoor pauper children. Although some outdoor children were admitted to workhouse schools in the North of England and also to Quatt Farm School in Shropshire, there is little evidence of this happening in other unions. Perhaps there are no children in the kingdom whom it is more essential to rescue from the mismanagement of their parents, and the bad example of their families and companions, than the children of out-door paupers, a class usually characterized by habits and vices disastrous to the morals of young persons, exposed to the contamination of their influence and society.

It is also likely that the union had negotiated a special scale of school fees for many years. The reports on education of pauper children also claimed that many outdoor paupers equated the level of school fees with the quality of education offered and several witnesses asserted that cost did not deter even the poorest pauper parents. The effectiveness of schools for working-class children is also uncertain.

Criticism was also extended to the imperfect English grammar used by school masters and mistresses, examples of which were recorded, with a degree of superciliousness, in the reports. Although the education of outdoor pauper children was always a subject of debate, so was the burgeoning financial costs of outdoor relief. Of course, as Finlayson claims, it is unsafe to see the COS as representative of charitable enterprises.

This had fallen to In , , children were thus relieved, while in , the numbers had fallen to , So, although Doyle pointed to his model union at Atcham reducing outdoor relief to one and a half per cent, unless the workhouse was enlarged or the union split, Brock felt that Swansea Union was unable to administer the workhouse house test to any meaningful extent. However, unions did respond to rising outdoor relief costs and accusations of fiscal profligacy.

In , Swansea union began recording weekly expenditure figures for outdoor relief alongside figures from the previous year. This involved the claimants being put to work between 9. They were allotted either breaking stones or picking oakum between the hours of 7. For this they would be paid a halfpenny per day for themselves and their wife and two pence for each child, to a maximum of 12 shillings per week and at least half the relief was to be given in kind, of which bread was the chief item.

The men were not allowed to smoke or swear and non-compliance could result in outdoor relief being withdrawn. If information concerning those in receipt of outdoor relief is sketchy, details about the subsequent lives of unsuccessful applicants for outdoor relief are almost non-existent. Doubtless, there were fraudulent claims, but the description below from the Royal Commission conveys the hardship experienced by many mothers and consequently, their children.

She will, if allowed, try to do this on an impossibly inadequate sum until both she and her children become mentally and physically deteriorated.

Pauper Children and Poor Law Childhoods in England and Wales 1834-1910

If she is lucky she struggles on till the children begin to earn. In many cases she gives up the hopeless struggle and drifts into the House. It is likely that many families who had been granted outdoor relief also found it inadequate. In a letter to The Cambrian , R.

Vaccination Act made free vaccination available as a charge on the poor rates. The latter was assumed to be brought back from local schools, where standards were not as particular as those of poor law inspectors. Boorman, David, The Brighton of Wales: There were no laws to protect these young workers until the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act in A petition to the House of Commons included signatures from leading physicians and surgeons of London hospitals who agreed that such people should not be kept for more than a brief period in any hospital established for the cure of the sick. Moses became a boarder at the Swansea Blind Institution in and his fees and all necessary clothes, tuition and boarding fees were paid for by the Swansea Union.

It appears that many families in receipt of outdoor relief needed to supplement it with help from other sources. This was also recognised by guardians; at one meeting in , it was recorded that had it not been for the charity dispersed during the preceding winter, the burden on the poor-rates would have been much greater. Secretary of the Landore Relief fund demonstrated.

Families who experienced financial distress also had to identify sources of assistance and, as a remark at a meeting of guardians demonstrates, this was not always straightforward. At times, guardians did help outdoor paupers with extra expenditure although it is problematic to analyse any particular rules or pattern which allowed this as the sources do not allow for more than informed speculation. Most cases involved negotiations between pauper, relieving officer and guardians. In it was ordered that clothes given to outdoor paupers were to be stamped with the union stamp and numbered as clothes were often the first items to be pawned by the poor in times of need.

Indeed paupers who left the workhouse wearing union clothes were liable to prosecution. Several applications from Neath Union, plus a plea from the Mayor of Aberavon, failed to persuade Swansea Union to pay for clothes to enable the children to attend school. Although her 15 year old son was earning seven shillings and her 12 year old son 5 shillings, Hannah Holland was nevertheless awarded four shillings and sixpence a week.

Sons gained and lost work, and guardians changed their minds over the slightest infraction. Women were at the sharp end of poverty, many having to supplement household income anyway they could; prostitution was sometimes the only marketable commodity left to mothers in need. The situation of Julia Thomas illustrates how a mother would endeavour to keep herself and her children out of the workhouse despite severe difficulties. Events such as Christmas, royal weddings, jubilees or particularly harsh weather could also generate generosity from poor law unions.

Extra relief of around sixpence or one shilling per pauper was generally given by unions at Christmas, although not all did the same. Outdoor paupers survived via an economy of makeshifts. In when Ann Thomas and her two young sons were deserted by her husband. These were areas without adequate sanitation which were perceived as dens of vice, crime and disease, often because they housed a substantial unpopular immigrant Irish community. Although there is a paucity of sources relating directly to the lived experience of outdoor pauper children, analysis of the areas which housed large numbers of outdoor paupers can enhance our understanding of their everyday lives.

One such area was Greenhill, on the north-eastern outskirts of Swansea town centre. In Green Row, up to 30 people a night slept in a two-roomed cottage without a privy or any sewers. John Bowen was not a pauper and his occupation was a shoemaker. It is not known how much relief Ann was awarded, but the fact that she lived with her parents was probably taken into account. In one house two widows with four children apiece lived together.

The aforementioned Mary Collins, aged 42, was the householder and June Clayson, aged 31 was, along with her children, recorded as lodgers. However, mothers left children in workhouses and also sent their children back to the cottage homes from which they had absconded. This of course could signify that mothers felt the institutions offered by unions were better than they themselves could offer, but the reports of the NSPCC also relate many tales of cruelty and neglect of children who were later taken into the care of guardians across England and Wales.

Annie Knight was allowed six shillings outdoor relief for 14 weeks while her husband was serving a gaol sentence for desertion from the army. Boards of guardians were very different bodies by the beginning of the twentieth century. Changes in legislation in the s and s meant that women and working-class men made up larger proportions of boards of guardians, although wealthy men and luminaries of civic society were still invited to participate.

However, upon his retirement, although Thomas Bircham had long campaigned for guardians to keep girls in cottage homes until they were older, he thought that changes in the poor laws should not lead to generous or indiscriminate outdoor relief, and this was a very similar viewpoint to those of his predecessor Andrew Doyle.

In , a poem was published a regional newspaper. This chapter explores aspects of child-saving, reform and containment via the charitable institutions to which poor law unions sent some of their pauper children. By far a more common strategy was the placing of some children of the state with private charitable institutions. Philanthropy was huge in nineteenth-century England and Wales and formed a large part of the work thought becoming for middle-class women. Within a year the house they had procured for the purpose was deemed to be too small and unsuitable.

Twenty girls had been admitted during that first year and as subsequent applicants had to be turned away, a fundraising campaign for a purpose-built institution was started. It is difficult to establish the criteria by which unions chose girls to go to the orphan home. If the two girls were without family, only the last two strategies could apply. This criterion for entry was one of many conditions detailed in its annual reports, although it is uncertain whether these rules were acted upon. However, the mothers of Sarah Fairchild, aged five, Elizabeth Parry, aged nine, Ellen Lowney, aged seven, and Ann Jones, aged five, were all inmates of the workhouse.

The Swansea orphan home, however seems to have been much more focussed on producing more able servants and had strategies in place to ensure that this outcome would succeed. Unlike poor law workhouses and cottage homes, the orphan home could choose their inmates. Some institutions wanted to keep girls as long as possible.

Ruth Holman of the Stockport Industrial School wrote of her girls: However, this view was not shared by the guardians of Swansea Union who, in resolved to discontinue payments for girls in the orphan home who were over the age of The family home at 8 Jeffries Place appears to have been fairly substantial, Mrs Jenkins and her three daughters lived in four rooms, whilst a boarder occupied a further two.

The available sources do not reveal where the Jenkins sisters went upon their removal from the orphan home, although it is probable that they were found a place in domestic service. However, the fate of Naomi Upton, who left the home in because of the discontinuation of fees from the Swansea Union is known. The payment of two shillings and sixpence weekly for Naomi Upton and Elizabeth Thomas was stopped in April as they had reached the age of In the census, she is recorded as having no occupation and her brother-in-law John was a plumber and gas fitter.

The family also housed a lodger who was a school teacher at the local council school. While this strategy of removing older girls from the orphan home would have generated criticism from Thomas Bircham and probably others, Swansea Union made substantial savings as a result of this measure.

Records show that she was still an inmate of the home at the time of the census. The reports also projects that deflections from accepted norms were not tolerated. These strategies imply that the management of the orphan home were intent on turning out clone-like servants who would be welcomed by prospective employers.

Unlike the two other establishments explored in this chapter, the orphan home girls were moulded for general service. Sentiment was also employed in an advertisement offering laundering services which used the skills learned by the girls to supplement the funds of the home. Former inmates were encouraged to return to the orphan home for leisure when they were placed in situations and, if between employments through no fault of their own, could pay to live in the home until they found another place.

Although free time appears to have been regulated, the girls were provided with treats and outings, and some girls returned at Christmas and other holidays. Collections were made at local churches which generated gifts of toys, fruit and books for the girls at Christmas, and other gifts, collections and outings were made throughout the year. Presents of new pennies, again like those given to the children of the cottage homes by John Llewelyn, were also mentioned as Christmas gifts. Treats and outings, although offered, were not at the forefront of the minds of campaigners who sought to establish training ships for boys.

The Havannah had been commissioned in , saw both war and peace-time service around the world and was sent to Cardiff in to be used as a training ship. The minimum and maximum age for joining a ship was 10 and 12 respectively and for leaving a ship 14 and 16, which meant an enforced stay of at least two years, and up to six years for some boys. In reply to an inquiry, the Local Government Board informed the guardians that they were empowered to pay for the maintenance of pauper children in a certified school or training ship.

Also eligible were children under 12 who had committed an offence punishable by prison and children under 14 whose parents were unable to control, and following the late nineteenth-century education acts, children who did not attend school regularly could also be admitted to industrial schools. Later acts also extended to the committal of children if their mothers were criminals or were thought to be involved in prostitution. The first pauper boys to be sent to Havannah were Charles James, aged 12 and William Whelan, aged The boys were taken to the Havannah training ship within two weeks of this resolution and the Swansea Union paid six shillings a week per boy.

Many training ships of the nineteenth century were seen as employing harsh and punitive regimes. Grigg claims that the discipline in training ships was harsher than in reformatories, although it is unclear whether he refers to the reformatory ships rather than industrial school ships. By the s the Havannah was attracting negative comments concerning its condition, as by this time the ship was around 60 years old. Cowan claims that this may be attributable to the difficulty in engaging teachers which led to the education on training ships being inferior to elementary schools.

From its inception a matron was a member of staff and generally the wife of the superintendent was visible. The inspection of listed a long string of offences and the subsequent punishments received by the boys, and he also remarked that illnesses were more prevalent.

For breakfast there was eight ounces of bread, some butter and a pint of porridge with milk, meat twice a week and mostly stew or soup on the other days, except Friday, when one pound of fresh fish and the same of potatoes was served, for supper the boys ate eight ounces of bread and jam with cocoa. Watson claimed that very few Havannah boys chose the sea as a career, whether this was because their training put them off the sea or it was inadequate is unclear.

His assertion that the navy had no need of industrial school boys as they could choose from so many others may have reflected the reality of employment for boys of blemished character. However, it does appear that many boys who were placed in reformatories or industrial training ships like the Havannah stayed within the law after they were discharged, and Jones also estimates that around two-thirds of boys from Welsh reformatories did not re-offend.

Nevertheless, some of the annual reports of the Havannah and letters, purported to have been written by old boys, suggest radical transformations to the supporters and potential subscribers of the ship. What was imagined as normal were middle-class values, but without middle-class advantages. The management of the Havanna h instilled into the boys the idea that responsible working-class citizenship would result in appropriate rewards such as enjoyable, yet respectable, treats.

In the evening the boys were taken to a local circus. The Local Government Board continued its support of training ships into the twentieth century. The ship had been sold for breaking up and the boys transferred to the Bristol training ship Formidable, and from there to a new naval training school that was being built at Portishead.

Lawrence to his old Captain Bourchier of the training ship Exeter in demonstrates that some boys benefitted from the regime. Unlike the many boys about which the central authorities bemoaned a lack of subsequent sea service, Lawrence did enter the service. Again there is no contemporaneous evidence to suggest similar abuse in either the Havannah or at Nazareth House.

- Short Order - A Collection of Speculative Fiction and Science Fiction Short Stories;

- THE PROBLEM OF THE CHILD-PAUPER.*.

- Affirmation Your Passport to Happiness.

- THE PROBLEM OF THE CHILD-PAUPER.* » 15 Jan » The Spectator Archive;

- Everlasting.

- Slavery And Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory?

It is possible either that Elizabeth was discharged from Nazareth house or that being grown up she was considered a help rather than an obligation. As the cottage homes in Swansea housed many children of the Catholic faith, it is likely that Nazareth House was seen as a destination for children requiring extra care, but there is no evidence to suggest that any non-Catholic children were sent there from poor law Union.

Discourses surrounding the appraisal of disabilities echo the anxieties concerning workhouse children being morally contaminated by their nearness to older, hardened and debauched inmates. Segregation of children from their parents and other adults was not solely a callous poor law device, but also sought to quarantine children from inmates perceived as vicious or idle. The veracity of inspections such as these had been challenged in Punch , which had depicted a poor law inspector touring a workhouse with his eyes shut.

Similarly, disabilities did not appear to rule out future employment either in the minds of the management of Nazareth House or poor law guardians. Although Sarah Donovan was described as a cripple and stunted in her growth, and it was agreed by both that she was to be helped to earn her own living by sewing. Fitzgerald because her mother had been sent to prison. It appears that some girls with challenging behaviour were also sent to Nazareth House. Margaret Ryan, who was the daughter of an outdoor pauper, was sent there in when her mother professed herself unable to control her, and Margaret stayed for around three years.

However, local priests and Catholic locals were, as elsewhere in England and Wales, often at odds with poor law establishments and management concerning the religious instruction of Catholic pauper children. Father Butler, who was the first Catholic priest to be elected to the Cardiff Board of Guardians, felt that it was impossible to instruct Catholic children about their faith in a workhouse or non-denominational industrial school.

Privately-run charitable establishments welcomed funding from the state purse. The Swansea orphan home for girls rejigged their regulations in order to keep the large percentage of girls who were funded by poor law unions, and indeed wanted to keep girls in the establishment until they were older. Mr Dale brought these children to live and work at New Lanark.

They were called Pauper Apprentices. A pauper was someone who was very, very poor, and an apprentice is a trainee or learner. These child workers were orphans or poor children from the large industrial cities who had no one to look after them. This practice of employing apprentices was very common in mills. It was cheap to feed and clothe them and they were considered to be suited to mill work. By the standards of the day, the apprentices at New Lanark were well-cared for by Mr Dale. What do you think? Swan Sonnenachein and Co. The important thing is not the system, but the manner in which it is worked.

Continental reformers and many of the up-to-date Progressive party in England seem to consider that you have only to devise a system that shall be impeccable on paper, and all will be well; whereas any one with practical experience will assert readily that with good men to work it almost any system will produce excellent results. This fact is strikingly exemplified all through the history of our present subject.

Chance on his very first page, "of any system which may be adopted must depend almost entirely upon administration. Although reform has followed upon reform—and at the present time no one defends the education of children in a workhouse—it is doubtful whether any existing system can show better results than did the Atcham Workhouse school more than forty years ago. There we see an inferior system succeeding simply by reason of good administration. On the other hand, bad administration will ruin the very best system that it is possible to devise. Bad as was the system of workhouse schools—that is of schools actually attached to the workhouse—its results compared favourably with those of the education then provided for the children of non-paupers.

In , for instance, the Bedford Guardians requested the Commissioners that the schoolmaster in their workhouse might teach reading only. Tufnell, an authority often quoted by Mr. Chance, wrote in the same year that "three months' education in a well-conducted workhouse was worth to the children almost as many years of such instruc- tion as they can get at home by attending village schools. The results of this education were so good that the work- houses were pestered with applications on the part of em- ployers who preferred ex-pauper children to any other class, and even to-day, in spite of the enormous strides made by public education, the training of pauper children is still in many respects superior to that which is received outside.

In the Report of the Royal Commission on Education denounced the workhouse schools and all their works, on grounds which Mr.

- Reviews in Food and Nutrition Toxicity: 1

- Lone Scherfigs Italian for Beginners (Nordic Film Classics)

- Heaven, or the Kingdom of God?

- Songs of the Earth: The Wild Hunt Book One

- Warrior Daughter

- Mennonite in a Little Black Dress: A Memoir of Going Home

- Emerging Worship: Creating Worship Gatherings for New Generations (emergentYS)