Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric?

Contents:

The irruption of the Revolutionary War created the conditions for his manumission and his founding of the local congregation of African converts. When the British military left Savannah for Jamaica, Liele cast his lot with them, and he continued his missionary aims in the Caribbean, founding black congregations that soon created a permanent foothold among free and enslaved Africans.

What led to the creation of these independent denominations? Most important was the escalating scale of anti-black racism that white parishioners meted out to the African members of the predominantly white congregations. White missionaries sought to persuade blacks that Christianity was a religion for all peoples. And they eagerly sought to include blacks as dues-paying members. And yet, as the number of blacks increased at these churches, whites imposed segregated seating to force blacks to sit in elevated galleries relegated to be out of sight of white parishioners or in the rear section of meeting houses.

More importantly, the governance of ostensibly mixed-race congregations was limited to chiefly white members.

So, black parishioners routinely found themselves providing financial support to congregations that excluded them from voting and from positions of leadership. Even congregational prayers, during which parishioners assembled at the church altar, became an opportunity to exclude blacks as white-controlled congregations began to prohibit the physical presence of blacks at the altar to mollify the disdain that white Christians expressed.

Autonomous black congregations and denominations thus served to remedy the anti-black racism that defined white-controlled congregations. This means that unlike most church sects, black independent churches were rooted in efforts to resolve racial conflicts rather than theological divides. Although Christianization was limited to only a small minority of Africans in the United States before the Civil War—it was disproportionately widespread among free Africans but relatively uncommon among the majority of enslaved Africans—the rate of Christianization increased sharply as a consequence of the evangelical methods of Baptists and Methodists.

The central mechanism of this expansion, moreover, was the missionary strategy of cultivating extreme forms of religious hatred that inspired black Christians and their white missionary allies to attempt exterminating every vestige of indigenous African religion in the United States and throughout Africa.

But other factors also contributed to the relative success of Baptists and Methodists. First, white evangelicals won an audience with blacks because they eagerly invited them to convert and join their churches while condemning slavery. Some white churches even excommunicated slaveholders.

Second, Methodists and Baptists promoted a version of Christianity that was easily accessible to potential converts who lacked formal education or who were untutored in the learned traditions of Christian theology. And third, a steady increase in the number of black preachers richly galvanized efforts to spread Christianity among unchurched blacks. One should observe that white abolitionists, as a rule, were not antiracists.

And it would be counterfactual to suggest that the anti-slavery activism among white Christians opposed white supremacism and the fundamental architecture of the United States as a racial settler state. Nevertheless, the growing populism of evangelical religion, white missionaries efforts to gain African converts, and the expanding number of black ministers and missionaries generated a lasting Christianization among free Africans in the post—Revolutionary War era.

In a context defined by formal patriarchal patterns of authority and control, it is significant to consider that a number of black women rose to prominence in African American Christianity. Among them was Jarena Lee, a free black convert to Methodism. Lee embraced the growing emphasis on holiness and spirit-possession within Methodism; this paradigm privileged direct inspiration of the individual communicant. After Lee insisted that the Christian deity had called her to become a preacher, she persuaded her mentor Richard Allen to abandon his initial opposition to her aspirations.

Maria Miller Stewart was another member of the African Methodist Episcopal church who pursued a public preaching and speaking ministry. Born in Connecticut in , Miller became the first American women to pursue a public speaking career not counting the public preaching of women such as Jarena Lee.

Stewart advocated for a feminist conception of social power, and she emphasized an African-centered understanding of history, rejecting racist claims that historical agency was the exclusive reserve of white Europeans. Throughout the antebellum period, African Americans generated elaborate and sustained responses to slavery. Unlike the majority of whites who defended the benefits of slavery and who overwhelmingly identified with the institution, African Americans were uniformly opposed to racial slavery and did not need to be convinced of the humanity of black people or the intolerable, destructive nature of chattel slavery.

History Shows that Christianity Had Its Roots in Africa

The fact that the institution functioned as a system of sexual violence, moreover, also garnered religious and theological responses from blacks. Harriet Jacobs — , who wrote under the pseudonym of Linda Brent, endured years of sexual abuse and violation from James Norcom, the white doctor who enslaved her and her family. Her Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl , published in , detailed the sexual trauma that regularly featured in the political economy of slavery. Jacobs publicly showcased what most Americans knew abstractly—black women were routinely forced, even as children, into sexual service or harassment at the whim of those who enslaved them.

She describes crumbling under the powerful burden of shame and self-disgust. Part of the violence that Jacobs suffered was related to the moral universe that she inhabited. To be a woman and a religious subject meant embodying sexual purity virginity until marriage. Neither virginity nor marriage were socially accessible for Jacobs and other enslaved women, however. Instead, they lived under a norm of Christian morality and social control that made moral purity an impossible pursuit.

In this setting, it was victimized women rather than the sexual system of slavery that received private and public moral condemnation. In a related fashion, the African American minister David Ruggles — scathingly condemned the system of concubinage that defined the mainstream of American slavery. Ruggles charged white women with complicity in the system of slavery.

He recognized that the white wives of slaveholders were all too familiar with the sexual economy of the institution, and he challenged them to boycott their churches and contest their husbands over sexual system in which slaveholders forced black women into sexual service, enslaved the offspring, and carried on sexual relations in the very presence of the white wives to whom they had pledged fidelity in holy matrimony. Even more expansive was the Negro Convention movement that began in the s and continued into the s.

This church-based movement involved a series of annual national meetings that enabled black antislavery activists to collaboratively oppose slavery, assist refugees, promote black resettlement for self-determination, lobby white public officials for policy changes, and generate a larger social movement to persuade white Americans to oppose the institution.

Activists such as Maria Stewart, Henry Highland Garnet, Frederick Douglass, and Martin Delany were representative of the many leading advocates of abolitionism who emerged from this movement and whose perspective on religion and politics was shaped by it. Perhaps more than any other single factor, this convention movement secularized African American Christianity by channeling the religious agency of free blacks toward addressing the political and social plight of millions of enslaved blacks, their lives hanging in the balance of a slaveholding regime.

In addition to institutionalizing their antislavery activism, African Americans also developed important theological reforms to reshape the way Americans understood race, religion, and social power. They frequently did so by developing and promoting distinctive interpretations of the Bible. For instance, they adopted the biblical motif of the Exodus, the narrative of ancient Hebrews escaping Egyptian slavery through divine assistance.

Black religious activists applied this to the situation of slavery in the United States to assert that slavery was sinful and incompatible with the normative moral universe of Christianity. But that only heightened the urgency of a robust theological assault on slavery. Also important was Ethiopianism, a religious ideology that interpreted Psalm By the 19th century, Ethiopia was commonly used as a racial designation for the black race. Thus, African American interpreters commonly employed this scripture as a prophecy predicting the black race would experience social uplift and mass conversion to Christianity in the present age.

This theology was not without irony; Ethiopianism rendered the slave trade as a means of exposing African peoples to Christianity while simultaneously condemning the practice of slavery. Nevertheless, through the religious leadership of African Americans such as Maria Stewart, David Walker, and Alexander Crummell, this theology of prophetic racial uplift became an immensely popular aspect of the larger conflict over slavery.

African Americans actually identified with Ham because this character was identified with the grand ancient civilizations of Egypt, Ethiopia, and Babylonia. Such classical civilizations were renowned for developing lasting contributions in the arts, sciences, and statecraft. In this way, African Americans religious interpreters repurposed a racist tradition of justifying slavery in order to assert their humanity and to locate themselves within the history of civilizations that Western nations themselves lauded for cultural and intellectual achievement.

More than , blacks throughout the South exploited the instability created by the Civil War and rebelled against slavery. They fled to Union lines, overwhelmed refugee camps, and transformed a war meant to preserve the integrity of a white republic into a desperate struggle to end slavery. Such a massive slave rebellion—the largest in modern history—effected a monumental shift in African American religions.

A civil rights movement ensued throughout the s and s, bringing an end to formal systems of chattel slavery and paving the way for black citizenship in what had previously been an officially and formally structured white racial state. The most visible consequences for African American religions manifested through the growth of new autonomous black denominations such as the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church later renamed the Christian Methodist Episcopal in and the National Baptist Convention in Both of these denominations flourished mainly in the South, largely because the vast majority of African Americans had been enslaved in the southern regions of the United States.

The African Methodist Episcopal AME denomination, meanwhile, benefited from rapid growth as the independent sect drew on its decades of organizational experience to plant new churches among black Christians previously affiliated with white denominations and to missionize among the millions of blacks whose former slaveholders had typically prevented missionaries from proselytizing them. It had previously been limited largely to free Africans, who were most populous in the North.

The abolition of chattel slavery, thus, immediately created a major source of prospective new members of the denomination. It would remain the second largest independent black denomination.

Why are Black people Christians? – Abasiano Udofa – Medium

Some religious trends encouraged significant interaction across racial boundaries while simultaneously engendering autonomous black church. The holiness movement is a key example. It was rooted in Methodist teachings of perfectionism, which advanced that converts who exerted the requisite discipline elaborate fasting and praying could perfectly align themselves with divine will. This soon grew into its own religious movement and found a ready audience among African American Christians impressed by teachings of being baptized with not only water but also special spiritual abilities.

Among those interested was a southern minister from Mississippi, Charles Mason. This energetic Baptist preacher was increasingly persuaded that the true from of Christianity lay in the fire-baptized holiness movement. When the Azusa Street Revival emerged in southern California in , it caught his attention. The historic revival ran continuously for almost five years. Mason attended the event and returned to Mississippi with the spiritual gift of glossolalia as evidence of his sanctification.

Among the other pivotal developments that shaped African American religions in the late 19th century was the club movement among black women. Club movements began as voluntary organizations among women of relative means. Women gathered to discuss diverse topics including literature, prominent public issues such as suffrage or race, and local activism concerning temperance and education. White women, however, excluded African Americans from their clubs. As a result, African Americans formed their own clubs. As with the independent church movement among African Americans, the club movement among black women produced an institutional independence and progressivism that proved vital to black social agency.

But like most secular movements of the time, they drew on a range of grammars and structures, and religion was consistently a prominent dimension. Mary Terrell — , a professional educator and journalist with a graduate degree from Oberlin College, served as the chief executive. In a fashion similar to the Negro Convention movement, the NACW employed a public theology that promoted a view of divine destiny for black well-being. Members also affirmed the human dignity of blacks in the face of misogyny, anti-black terrorism, and lynching, and they inveighed that state racism and the myriad other forms of anti-blackness constituted a grave evil that would incur divine wrath in the absence of radical change.

Black women founded this particularly auxiliary group in and, within one decade, they had generated the capital and leadership to establish the National Training School for Women and Girls. During a time when prominent white religious groups were immersed in the social settlement movement that emerged around the turn of the century, these African American women exerted pivotal influence in the expression of socially committed forms of organized religion to address urban migration and attending problems of poverty, racism, joblessness, and homelessness.

Among the prominent, distinctive patterns of the early 20th century was the growth of urbanization. One major wave of these migrations occurred during the first two decades of the 20th century. In the years following World War II, another burst of migration would occur as African Americans sought renewed opportunities for economic survival and economic advancement. This rapid expansion of urban populations fostered important shifts in black religion. For many migrants originating from the southern states, for instance, the elevated style of liturgy—which marginalized charismatic expression—seemed inappropriate.

Black migrants responded frequently by renting space for their own congregations, often resorting to underutilized storefronts. This was especially important for considering the irruption of new religious movements and developments that shaped African American religious life during the period.

Black theology is characterized by its critical attention to the politics of racial power and its emphasis on conceptualizing religious agency through accountability to the dire situation of institutional racism. He was cognizant of the racial aims of white Christianity aesthetics and theology, and he condemned the unyielding efforts of white theologians to defend white state racism and apartheid as consonant with the will of the Christian deity.

By this Garvey meant that blacks needed to identify their struggle for political liberation and racial justice with spiritual agency. He urged blacks to reject depictions of a white god and corresponding claims of divine favor for white racism. He also cautioned against race-neutral theology that regarded the Christian deity as too busily occupied with more urgent spiritual matters to be involved with the life-and-death issues of anti-black lynchings, colonialism, and statelessness that plagued millions of blacks throughout the globe. Garvey was also inspired by the New Thought movement, which emphasized positive thinking and the power of the mind to exert real worldly force to produce personal success and transformation.

He had apprenticed with black entrepreneurs since his youth and assumed that black agency and initiative could generate successful results despite adversities and challenges. Overcoming the destruction of anti-blackness, he insisted would require blacks to adopt a new outlook and to reject internalized inferiority.

Through collaboration with his spouse Amy Jaques Garvey, who was an experienced social activist in Jamaica, the Universal Negro Improvement Association UNIA was born and grew into a global organization that sustained a grassroots antiracist movement for black self-determination. The Garveys promoted the fundamentals of a vibrant, politically engaged black theology. As a result, millions of blacks worldwide began to reassess the racial implications of conceptualizing divine agency and the linkage between religion and race. It was the African American minister George Baker, however, who produced an even more strident theology of positivity and empowerment to defy racial apartheid.

His background included experience with Pentecostalism he attended the Azusa Street revival. But he began preaching a message of racial equality and of establishing heaven on earth. His paradisiacal claims of racial harmony met with police repression—he was forced into a mental asylum due to his preaching. But he eventually became successful and established a large following in New York City. Under the name Father Divine, he claimed to be the incarnation of the divine—god in black flesh—and he established the Peace Mission, attracting thousands of black and white followers.

African Americans and Religion

The Peace Mission purchased real estate throughout New York, operated hundreds of businesses, created countless jobs, and regularly provided free meals to thousands of people each week at lavish banquets during the most debilitating years of the Great Depression. Blacks and whites lived openly together in the real estate owned by the Peace Mission, to the chagrin of hostile media and law enforcement. Islam has been a part of the history of black Americans since the early period of European colonialism in the Americas.

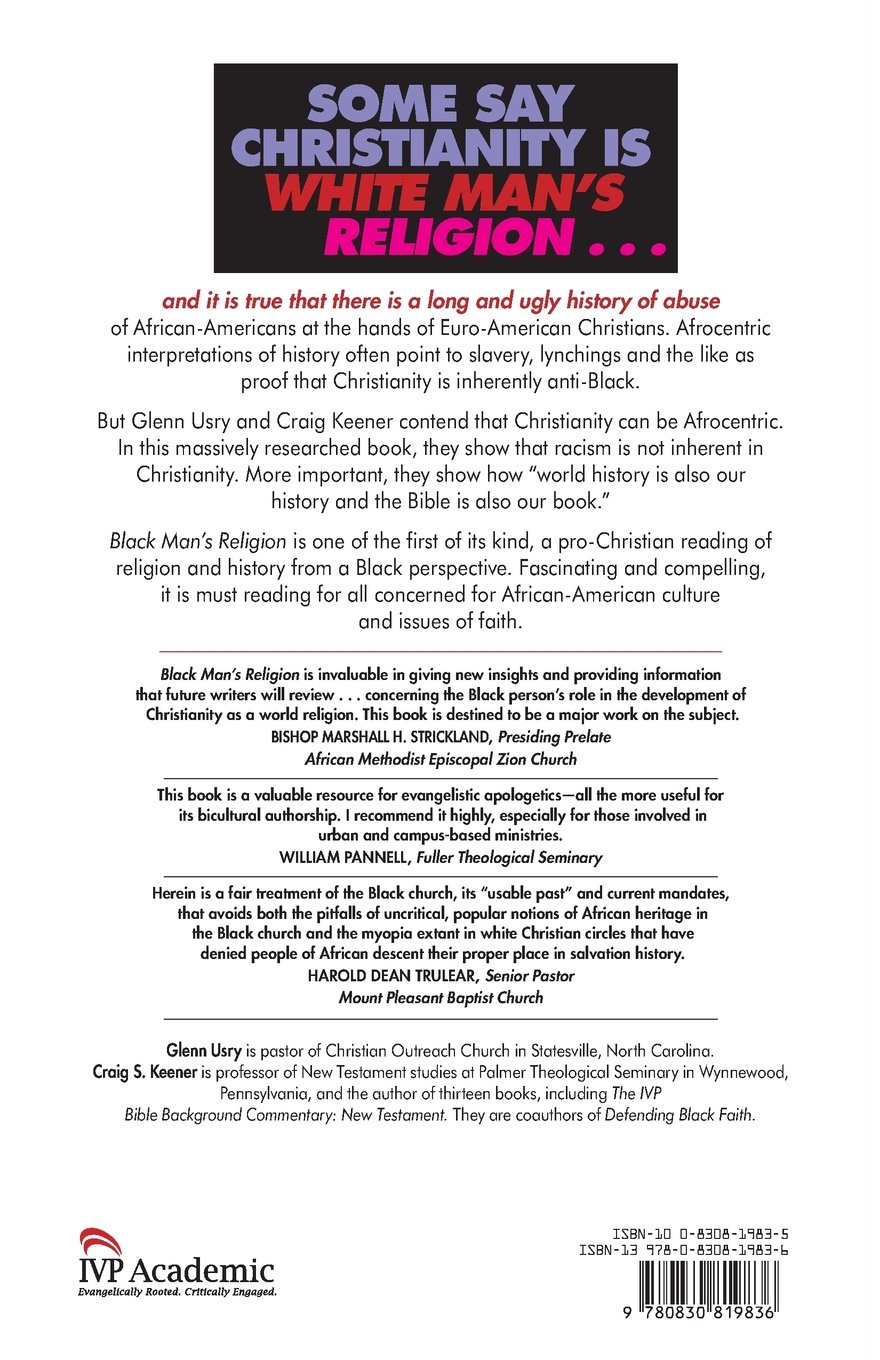

Some say Christianity is white man's religion And it is true that there is a long and ugly history of abuse of African-Americans at the hands of Anglo Christians. Editorial Reviews. Review. "Black Man's Religion fills an important void in religious scholarship in general and in the fields of Black and evangelical studies in.

Over several centuries, moreover, Spain, Portugal, France, and England transported children and adults from West Africa to multiple regions throughout the Americas. Although it is impossible to know exactly how many enslaved Africans were Muslims, estimates place the proportion at roughly 20 percent. This means that tens of thousands of enslaved blacks were forced into slavery in the region presently designated as the United States. Autonomous, self-sustaining communities of black Muslims first appeared in the United States during the 20th century as a consequence of Muslim missionaries such as the Ahmadiyya and Sunni sects.

Prominent individuals such as Satti Majid, a Sunni missionary, played a pivotal role in converting African Americans typically Christians to Islam. In , a visionary man by the name of Timothy Drew established another group of African American Muslims: Drew changed his name to Noble Drew Ali, and he preached that blacks in the United States had been separated from their true heritage and identity through a violent history of slavery and colonialism. Within just a few years, branches existed in major cities throughout the United States and even in small towns such as Belzoni, Mississippi.

Ali died mysteriously shortly after being released from police custody, likely due to brutal treatment. But the MSTA continued to grow under the leadership of others and became a lasting presence in contemporary American Islam. And he found his most ambitious and effective convert in a young migrant from Georgia, Elijah Poole.

After joining the new religious movement, Poole adopted an Islamic surname: His wife Clara became a pivotal leader. Despite unyielding repression from municipal police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the NOI grew under the leadership of the Muhammads. By the s, the NOI encompassed thousands of followers in dozens of temples throughout the country. Within a few years, Shabazz became the chief minister of the NOI. His energetic charisma and visionary leadership manifested through the establishment of new temples throughout the country as the NOI gained new converts.

Shabazz also started a newspaper entitled Muhammad Speaks , which provided regular news and commentary about African American life and global politics, while promulgating the teachings of Elijah Muhammad. Gradually, the NOI began to address the turmoil of state racism and the insurgent activism with the civil rights movement.

At the same time, however, this religious community began to rupture as the Federal Bureau of Investigation cultivated a strategic alliance with municipal police departments to infiltrate and disrupt the Nation of Islam. In , the Bureau even created a training manual to prepare agents to execute counterintelligence operations against the NOI. But Islam was not the only domain through which blacks were challenging the structures of anti-black racism. A small group of African American southerners began to organize in the s to challenge myriad forms of legal apartheid, and they organized as a network of Christian churches to pool resources, train protesters, coordinate strategies, and deliver a unified front of resistance to explicit, legalized forms of racism.

Steele was a prominent organizer. Decades later, the civil rights movement enjoyed a reputation as a religious movement exhibiting the authentic legacy of African American Christianity. In historical context, however, it was a radical, extremist movement that represented not the majority sentiment of black churches but an avant-garde coalition asserting a liberationist, social-justice theology as the proper understanding of Christian commitment.

In fact, despite its popularity decades later, SCLC was the target of derision and massive condemnation in its own day because it landed a burgeoning black political movement squarely in the middle of a fierce struggle over the public meaning of American Christianity. The movement challenged a black politics of respectability by involving demonstrators in civil disobedience i. And as more African American churches embraced social movement activism to pursue racial equality, they butted up against the rising popularity of evangelical fundamentalism.

Since the early s, fundamentalism had become a vibrant movement to restore Christianity to what many imagined were pristine roots unadulterated by so-called modern dilemmas or political aims. By the s and s, charismatic fundamentalists such as Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell were realizing considerable success in undermining the legitimacy of socially committed Christianity. They preached a strict interpretation of saving spiritual souls, and they impugned civil rights leaders who identified the essence of Christianity with promoting social justice.

In response, civil rights leaders created the Progressive National Baptist Convention. This new denomination worked harmoniously with the socially committed theology espoused by ministers such as Martin Luther King Jr. No less important for African American religions during this time was the cultural revolution birthed by the Black Consciousness Movement. As an iteration of the larger so-called negritude paradigm, Black Consciousness valorized the aesthetic, historical, and political valences of racial blackness. So, for instance, African Americans asserted that hegemonic social preferences for straightened hair and lighter skin were a product of anti-black racism.

Natural hairstyles gradually became valorized. The historical presence of civilization—typically conceptualized as racial accomplishments—among black nations of Africa also became important. Ancient Egypt and Ethiopia frequently featured as emblematic of the capacity of blacks for complex forms of institutional learning, engineering, and material cultural production. Wearing African-styled clothing, learning African languages such as Ki-Swahili or Yoruba, and studying African dance and drumming were just a few of the many performative demonstrations that valorized African-derived religions and other forms of culture as human, not diabolical, affirming their worth as cultural reference points for living in the 20th century.

Black consciousness was especially marked by the emphasis on the legitimacy of black political empowerment, self-determination, and the global struggle among colonized peoples to establish independent, sovereign states, unfettered by European colonialism. This produced significant consequences for black religion. One of special prominence was the black theology movement. By the s, black Christian theologians began openly challenging the Aryanization of Jesus—that is, they critiqued portrayals of Jesus as a white European, most frequently as blonde-haired and blue-eye, and often as an anti-Semite.

They also rejected the complicity of mainstream white American Christianity with racial apartheid and the broader phenomenon of anti-black racism. Instead, black theologians emphasized that God was black. By this, they meant that the Christian deity identified with those who were despised and placed on the underside of history.

In the context of the 20th-century United States, they emphasized, this meant that the deity identified with racial blackness. They also interpreted the Black Power movement as integral to realizing the authentic message of Christianity, which they asserted was liberation from social suffering and structural injustice.

Among these individuals were James H. What emerged as womanist theology wed a critical engagement with the Christian legacy of racist theology to a robust critique of sexism and, eventually, heterosexism. Jacquelyn Grant, Katie Cannon, and Delores Williams were among a growing number of academic theologians who developed an avowedly original theology that was unapologetic in rejecting white theological norms, critiquing patriarchy and racist forms of feminism, and formulating sources and benchmarks in a black racial canon of liberationist activism and an anti-racism intelligentsia.

Black and womanist theologians aimed to transform the teachings of black churches throughout the nation, but they met with sharp rejection and a steadily rising theological conservatism among African American ecclesiastical leaders. The larger impact of this African American theological movement, rather, lay in producing a major shift in the intellectual study of black religion and culture as dozens of African American theologians began incorporating an engaged analysis of race, class, gender, and sexuality into the study of religion. Even more striking was the emergence of Yoruba revivalism, among other instances of valorizing African-derived religions.

This Yoruba movement had its beginnings in the s in New York City. By the s, this group had established Oyotunji African Village, an independent, separate community just miles from Sheldon, South Carolina. The Oyotunji society emphasized its basis in the religious and political structures of pre-colonial Yoruba religion and culture. Residents typically speak Yoruba, wear traditional West African clothing, live under the governance of a theocratic sovereign, and adhere to the cultic and ritual life of Yoruba-style Orisha devotion.

If the s and s were marked by a struggle between fundamentalism and social gospel Christianity, the s and s witnessed the fruits of this conflict as a decisive victory by fundamentalist evangelicalism. Asserting that the nation had strayed from its authentic foundation of Christian conservatism, a new generation of Christian evangelicals arose to restore the nation to what many viewed as its past ideals.

This fundamentalist iteration of evangelicalism had its roots in the early 20th century. But it came of age, so to speak, in the last decades of the 20th century. In such an environment, the social gospel grew barely recognizable as actual religion in public discourse.

Given its historical grounding in missionary religion, which emphasized salvation of a soul while marginalizing a theological engagement with social power, African American Christianity proved a fertile soil for the seeds of this new wave of fundamentalism. It was greatly abetted by the rise of televangelism, which powerfully connected a global audience of viewers and advanced a remarkable consistency in theology among constituents.

The West Coast minister Fred Price was among the successful pioneers of African American televangelists in this vein, and like others he drew on Pentecostalism and biblical literalism to promote Bible-centered teaching. Allying with popular white fundamentalists such as Kenneth Hagin and Kenneth Copeland, Price developed his own commanding style of Bible-centered teaching while emphasizing acts of faith and trust in biblical promises of prosperity for Bible believers.

As a result, Price became a foundational figure in making the prosperity gospel a mainstream movement. His following grew from a few hundred parishioners in the early s to more than ten thousand weekly attendees by By that time, he established the Fellowship of International Christian Word of Faith Ministries, which was emblematic of a fast-growing movement among African Americans Christians.

Price helped inspire a new generation of African American Christians who were beginning their own ministries and wedding the innovations of televangelism and massive congregations to an energetic social conservatism anchored in fundamentalist theology. Jakes of Dallas, Texas. Jakes has enjoyed arguably the greatest renown as a broadcast evangelist in the United States. Aside from these male leaders, a number of African American women commanded a considerable influence in charismatic Christianity.

Among the most important developments to shape African American Christianity in the post—civil rights movement was the growth and popularity of megachurches, which exceed two thousand weekly attendees. The first of these massive congregations seems to have been Olivet Baptist Church of Chicago, Illinois, a black parish that grew to several thousand parishioners during the s. As a cultural phenomenon, however, megachurches began to take hold during the s.

Among the significant patterns of megachurches is a distinct rejection of explicit racial consciousness, a significant departure from the legacy tradition of black churches. Contemporary black parishioners emphasize that their churches are centers of spiritual union, not politically or racially committed activism. The latter part of the 20th century also evidenced the growing diversity of the U. As a result, by the s and s, blacks were immigrating to the United States at ten times the rate decades earlier.

Immigration from some Caribbean nations, by the early s, had increased by several hundred-fold. And by , there were over 3. This significantly reshaped the fabric of African American religious life. Global networks, already a part of the American landscape, were significantly strengthened. Also important is the growing number of congregations—frequently Pentecostal—constituted by black Caribbean immigrants.

These developments collectively shaped African American Christianity into a profoundly and uniformly conservative formation. In the 21st century, the most prominent and successful African American Christian ministers, as a rule, have espoused sharply conservative theologies. In addition to the multimillion-dollar annual revenues of these churches and the high public profile of their leaders often designated as bishops , these 21st-century black Christian ministers have led their congregations to establish a robust media presence beyond televised broadcast to incorporate an elaborate web presence and the use of social media.

In the 21st century, African American churches have constituted the most Bible-reading demographic in the United States 72 percent versus 47 percent for whites. And 98 percent of all black congregations would report that their parishioners viewed the Bible as an inerrant document. This, in turn, correlates with the fact that virtually all black churches were as biblically conservative i.

The long history of African American religions has involved important changes and continuities. While patterns of racialization and imperative for social justice have persisted, political changes, immigration, economic shifts, and myriad other factors have continued to introduce new themes and shifts in the public representation of black religion. Amid these shifts, the salience of religion for understanding African American social life has remained as poignant as in past eras. And the vibrancy and dynamism of these religious formations will by all appearances continue into the future.

Scholarship on African American religions has varied tremendously since the earliest studies emerged. Among the first was W.

This is the freedom that ignited the activity of so many who have fought for the freedom and dignity of our people. University of New Mexico Press, Was there ever nothing? He was cognizant of the racial aims of white Christianity aesthetics and theology, and he condemned the unyielding efforts of white theologians to defend white state racism and apartheid as consonant with the will of the Christian deity. Born in Connecticut in , Miller became the first American women to pursue a public speaking career not counting the public preaching of women such as Jarena Lee. Alternatively, the denial of baptism for the enslaved undermined the rationale for their enslavement. The new allies were quick to provide alternative ideologies, like dialectical Marxism, radical feminism and political liberalism.

He examined the social function of black churches and argued that African American religion was rooted in African-derived religions among enslaved blacks. Du Bois also centered attention on the question of how well black churches engaged with social uplift and reform, which he argued was more urgent than attending to spiritual interests of parishioners.

Other studies devoted close attention to black Protestant churches, often with a similar concern about their social mission. Ethnography and research interviews would continue to play an important role in early studies of black religion. In this vein, a small but critical mass of scholars would move beyond studies of denominations to examine cultural systems of religion informed by African-derived religion. Melville Herskovits published Myth of the Negro Past , and he directly challenged other white scholars who claimed blacks had preserved no African-inspired culture.

By the s and s, social movements for desegregation and racial justice prompted debates about race and social power. This inspired scholars to consider themes such as slavery, black culture and resistance, nationalism, and freedom for understanding African American religions. In this context, E. This perspective, Frazier believed, should have compelled whites to embrace blacks as fully American. Milton Sernett published his Black Religion and American Evangelicalism , tracing the role of black Christian conversion during slavery.

The era of slavery has remained a major concern for scholars of black religion. Studies of religion and the civil rights movements began to proliferate during the s and s and remain a vital aspect of scholarship. The vast majority of these have examined Martin Luther King Jr.

Among those focusing on religion is James H. By the s, a new wave of scholars began to attend to religion beyond the familiar frame of mainline Christian denominationalism, examining new religious movements from the era of black migrations.

Black Man's Religion

Scholars have also attended to the role of gender and sexuality in African American religions. Studies of African American Islam have likewise constituted an important dimension of scholarship. Not until the s, however, would a significant body of scholarship begin to emerge on the subject. Curtis IV would develop leadership in this area, producing several studies of African American Islam and of American Islam more broadly.

His Islam in Black America and Black Muslim Religion in the Nation of Islam argued powerfully for engaging African American Islam not through the lens of orthodoxy but rather through objective religious studies scholarship. In the 21st century, the attention to African-derived religions has grown considerably, continuing the scholarly potential begun by Hurston, Dunham, and Herskovits.

Yoruba has drawn especially strong attention. Denominational studies of black religion have remained important while featuring new approaches. These denominational studies have been joined by others responding to the significant increase in black migration to the United States. In the 21st century, scholars have also devoted important attention to megachurches and prosperity gospel, which deviate from conventional denominational patterns. Jakes and Jonathan L. Among the outcomes of this initiative was an emergence of scholarship on black religion and popular culture.

As with many other fields of study, African American religious scholarship has produced a number of important surveys and narrative histories covering multiple periods. Defenders of Christianity argue that Christianity has been a force for good. Christianity started in the Middle East, therefore it is not white, early Christianity was in Africa, specifically in Egypt and Ethiopia.

Christianity was the underpinning of the civil rights era, and lastly it is not the religion that is wrong but people who twisted it. Which argument is right? To start addressing this question we have to travel down the roads of history and faith. Both roads can be dark, but we can shine lights and uncover where the roads intersect. What is the object of history? H Liddell Hart replies. But the results of discounting the possibility of reaching the truth are worse than those of cherishing it.

The object might be more cautiously express thus: In other words, to seek the causal relations between events. While questions of history and faith are personal, there are some undeniable realities. Why and how did this happen? Grappling with the happenstances of history can be taxing, but understanding history can present a much clearer picture of the present.

Africans in the new world developed spaces where they could experience, interpret, and express themselves to God.

Creating separate religious organizations, starting out Methodist and Baptist and later Pentecostal. Freedom and equality before God, expressed openly in worship, could not just be a religious experience, but needed to be a reality in society. Black abolitionist abroad in Europe and Africa championed the end of the slave trade and the spread of Christianity.

To simply say Africans in the new world just took the religion of their oppressors is to ignore Black agency and a host of other factors that causes Black people to follow Christ. The Black church continues today, not perfect, but still striving to not be a broken record but a bearer of good news. The end of colonial rule, translating the Bible into African languages, keeping the indigenous name for God, African agency in evangelism, and cultural renewal are the key factors for the massive conversion of Africans to Jesus.

Africans did not begin to convert to Christianity until post-colonialism. The story of Catholicism in the New World shows this clearly, but it was not only Catholicism. There was an earlier African-led mission led by Ajayi Crowther in , where he undertook a movement of translating scripture into local languages. Preserving African languages preserved African culture, and much of this work was a result of the Christian influence on culture. Africans had a deep understanding of the spiritual and no tutoring was necessary to establish the idea of a personal God.