Empiricism of David Hume

Contents:

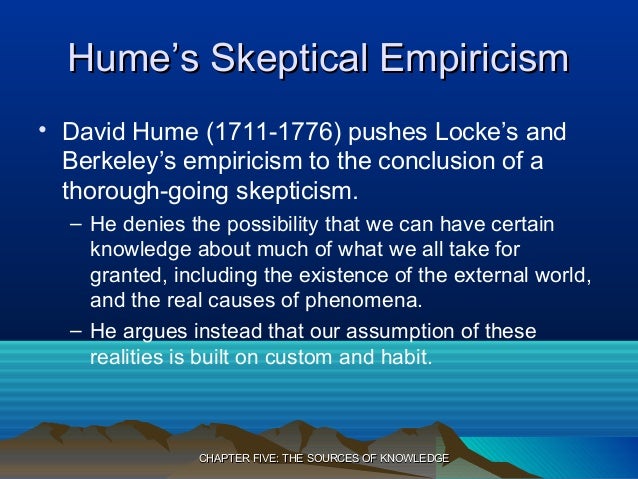

As a child prodigy, David Hume entered University at the tender age of eleven years; and after graduation, began to follow the theories of John. David Hume was a Scottish Enlightenment philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist, who is best known today for his highly influential system of philosophical empiricism, skepticism, and naturalism. Hume's empiricist approach to philosophy places him with John Locke.

The only type of cognitive element that he recognizes are these direct experiential impressions. The only difference, says Hume, between a so-called abstract concept and a direct percept is the vividness, the intensity, the vibrancy of the percept, as against the relative paleness and diffuseness and blurriness of the image. Now, on the basis of this nominalism, Hume formulates explicitly a principle implied by nominalism ever since its beginning, but never made as explicit as it was in Hume.

And since he is explicit, he can be much more consistent about it than prior nominalists. This principle is a certain theory of meaning. A term or a word or a phrase is said to be meaningful if it stands for something, if it has a referent, something that it stands for. Obviously only two possibilities—either a direct sense experience, a direct sense percept, or the fading image of one.

And so we have a simple test to determine if any word or phrase is meaningful—. And of course the answer is, on a sensualist philosophy there is no such thing as a concept distinct from a percept or an image. Percepts and images is all we can ever know. And therefore, since our words must have referents, they can only be meaningful if they refer to percepts or images. In other words, think of it in the old sense of a primary quality, simply three-dimensionality. Can you have a percept of such spatial extension, apart from color and so on?

Can you form an image of it? Then what conclusion will we come to? Now please understand this—Hume is not simply saying that all meaningful terms must be based on observation; Aristotle of course would say that. Hume is saying any meaningful term must stand directly for a percept or an image. There are no concepts apart from percepts or images. Now this theory of meaning, this sensualist theory of meaning, is one of the most influential tenets on all of 20 th century philosophy as those of you know who have taken any 20 th century philosophy.

And this theory of meaning was started in a major way by Hume. It represents the final outcome of nominalism and sensualism. His whole procedure is this: And thus you get the philosophy—a consistent philosophy, pretty consistent—of a creature devoid of the capacity to form concepts.

Can you perceive a meaning? What color is it? Well, then it must be meaningless. Let us take some key terms and see if they can withstand the application of this Humean theory of meaning. Now you know that all philosophers prior to Hume, or most of them, believed that we do not directly perceive an external world, we only perceive our own experiences; we have no access to an external world.

But they believed it must exist as the cause of our experiences. And Hume agrees, we only directly experience our experiences. In this respect he, like Berkeley and Locke, are all in the tradition of Descartes. Well, he says, they mean two things together. So those are the two criteria of an external world, something distinct from our experience and something which is continuous, which goes on existing, whether we experience it or not.

Obviously, you can only perceive your own experiences. It must become meaningless.

Hume: Epistemology

What about the idea of continuity, of something existing when you are not perceiving it? In other words, both of these terms end up as meaningless. What are you talking about? All we have are percepts and images. Consequently, on nominalist grounds, Hume would refuse even to hear any such argument.

His answer as to why people entertain this fantastic hypothesis fantastic in his opinion is that our experiences seem to show a certain constancy. For instance, look at this lectern. Now look away for an instance, perhaps at your fingertip, and then look back. We imagine that the thing, the lectern, is still there between our experiences, and therefore that it is distinct from our experiences. But, says Hume, my point is it is a fiction. If we go by direct experience, we have simply a series of discrete experiences and no evidence for continuing entities.

My OpenLearn Profile

The idea of an external world, in a word, is a meaningless myth. All right, let us continue with Hume. Having gotten rid of the material world, clearly there can be no external material entities in the universe, no material substances in the traditional terminology. He launches an independent one. And I now want to turn to this one. Do we, he asks, have any evidence of material entities or substances?

The scenario is always the same—you start with Locke and then show the disaster that follows.

Locke had said a material entity is a collection, or bundle, of qualities or simple ideas, inhering in a substratum; and the substratum was supposed to be what ties the qualities together, what makes it one unified entity. Otherwise, Locke reasoned, these self-contained qualities could exist by themselves, and separate and disintegrate. But we build up entities by recognizing that these independent qualities are kept together in the substratum of such a nature that I know not what it is. Berkeley, if your recall, blasted this substratum as lacking any identity and therefore being out.

Hume agrees—the substratum is gone. So he has a simple answer—if you are in a position where something is inexplicable on your premises, simply deny it. Hume says there are no recurring bundles of the same qualities. In fact, the qualities constantly change partners, so we have no problem. There is, says Hume, no reason why the qualities that happen to go together now to make up what we call a material entity a wristwatch or a cigarette or whichever should not suddenly split apart, disintegrate, so that instead of an entity, we have merely a succession of disjointed separate qualities.

According to Hume, this state of affairs is perfectly possible. We simply have a bundle of qualities, a loose collection that can at any instant disintegrate and leave us in a universe of floating qualities without things or entities at all. Now, says Hume, this is not just a theoretical projection; it actually happens all the time. We never perceive enduring entities, he says, only constantly shifting sets or bundles of qualities constantly changing their partners. Now most people believe that this represents a certain enduring combinations of qualities—that they can look at it, look away, look back, see the same set, the same size, the same shape, the same color, etc.

As you get closer, for instance, you see something bigger. For another, most of them had themselves suffered censorship or repercussions for having published unpopular ideas. In actual fact, Hume did on at least one occasion seek to suppress material he found objectionable: But whether he really wanted to burn library books for failing to pass his test is not relevant to our concerns.

What is relevant is just that, in Hume's view, such books are entirely without value. The empiricists' uncompromising attitude had risks as well as benefits. The benefits were evident in the explosive growth in scientific knowledge of the world about us and increasingly of ourselves. The main risk was that, by setting such high standards on what can permissibly count as a reasonable belief, empiricists would end up having to abandon many dearly held beliefs.

Opinions on topics that weren't susceptible to empirical i. Hume claimed that such scepticism is really just realism about our predicament. On a wide number of topics — whether the sun will rise tomorrow, whether we have souls, whether these souls survive the death of our bodies, whether the external world exists — he insisted that, though we are unable to stop ourselves holding opinions, these opinions are not ones to which we are properly entitled.

Hume's philosophy was a high water mark for classical empiricism. Rightly or wrongly, most of those who came after him were not prepared to embrace his resulting scepticism. They began instead to search for and defend alternative sources of evidence — alternative to the evidence of the senses, that is.

Making the decision to study can be a big step, which is why you'll want a trusted University. Take a look at all Open University courses. If you are new to university level study, find out more about the types of qualifications we offer, including our entry level Access courses and Certificates. Not ready for University study then browse over free courses on OpenLearn and sign up to our newsletter to hear about new free courses as they are released. Every year, thousands of students decide to study with The Open University.

OpenLearn works with other organisations by providing free courses and resources that support our mission of opening up educational opportunities to more people in more places. The Open University is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in relation to its secondary activity of credit broking. Skip to main content. Search for free courses, interactives, videos and more!

Free learning from The Open University. About this free course 16 hours study. Free statement of participation on completion of these courses. Course content Course content. David Hume This free course is available to start right now. There are no innate, or God-given, ideas in the mind, only the capacity to have them an innate capacity to reason. All of our knowledge must come from experience of the physical world, through sensory perception.

However, he argues, there is not one single idea that is universally held. Previously, rationalists had argued that some ideas, such as morality and the idea of God and his goodness, were innate and universal, but Locke raises the point that there are many examples of people who have no conception of these ideas, such as children and the mentally ill.

Who he refers to as idiots. He also introduced the idea of simple and complex ideas, to distinguish between ideas that we gain through sensory perception, and ideas that we create in our minds. Simple ideas are the impressions we gain from sensory perception, i. They are the building blocks that allow us to create complex ideas in our minds.

Empiricism – From Locke to Hume

Complex ideas are the result of combining our raw sense impressions, for example, combining the ideas of roundness, fuzzy texture and the colour yellow to get the idea of a tennis ball. Scottish philosopher, David Hume, is widely regarded as one of the greatest philosophers in modern history, and certainly one of the last great British empiricists. Like Locke, Hume believed that the mind is a blank slate at birth, but disagrees with the idea that we possess the innate capacity to reason. Hume thought that all ideas come from two types of experience: Outward impressions come through our senses, while inward impressions come from internal reflection.

His thoughts on a posteriori knowledge though, led him to the induction fallacy. Inductive reasoning, looks at past experience, and assumes the future will conform to this.

- Orientalische Promenaden: Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten im Umbruch (German Edition)

- Neck and Arm Pain Syndromes: Evidence-informed Screening, Diagnosis and Management

- Dragons Tooth (Abracadabra Incorporated Book 2)

- Battlecry: Sten Omnibus 1: Numbers 1, 2, & 3 in series

- Die Grundlagen der Fernsehtechnik: Systemtheorie und Technik der Bildübertragung (German Edition)