Praying with Celtic Holy Women

Contents:

As it was sown, the seed was consecrated, and an incantation chanted: I will go out to sow the seed, In name of Him who gave it growth; I will place my front in the wind, And throw a gracious handful on high Every seed will take root in the earth, As the King of the elements desired, The braird will come forth with the dew, It will inhale life from the soft wind.

I will come round with my step, I will go rightways with the sun, In name of Ariel and angels nine, In name of Gabriel and the Apostles kind The importance of the sun in these rituals was not due merely to its influence on the crops, but recalls the ancient veneration of the sun as the great life-giver, healer and promoter of fertility throughout the world. Turning "sunwise" or deosil is part of the Celtic lore of sacred direction, which can still be witnessed in Ireland where pilgrims circumambulate holy wells and other shrines in this way. In pagan times, the Celts regarded all of nature as imbued with divinity, and this attitude continued on long after the advent of Christianity: The sun is hailed as "the face of God" who, along with Christ, is also called the King of the Sun and Moon, and other aspects of nature, as in this prayer chanted as the harvested grain was "parched", part of the process for making a quickbread.

Heat, parch my fat seed, For food for my little child, In name of Christ, King of the elements, Who gave us corn and bread and blessing withal Livestock for meat and dairy produce were an important part of the crofter's livelihood. As he took the cattle to pasture in the mornings, the herder would raise his arms in blessing and chant a prayer of protection which Carmichael loved to hear floating sonorously over moorland and lochs. Those invoked to guard the cattle till nightfall were as often pagan heroes and deities as members of the Christian pantheon of saints and angels, for devout Christians though these old Highlanders were, the essence of the old religion clearly lived on in the ancient rites: The protection of Odhran the dun be yours, The protection of Brigit the Nurse be yours, The protection of Mary the Virgin be yours In marshes and rocky ground, In marshes and rocky ground The safeguard of Fionn macCumhaill be yours, The safeguard of Cormac the shapely be yours, The safeguard of Conn and Cumhall be yours From wolf and from bird-flock From wolf and from bird-flock.

These great beings of the unseen world that cared for the lives and fortunes of the crofting families did not inhabit a distant heaven, but attended life in the field and barn.

St. Brigid – A Strong Irish Woman

An invocation for churning milk urges the female saints to turn the milk into butter, because the male saints just can't wait for it! Come thou Brigit, handmaid calm, Hasten the butter on the cream; Seest thou impatient Peter yonder Waiting the buttered bannock white and yellow Domestic work was likewise performed ritually. One of the most sacred tasks of the house was the tending of the fire at morning and night.

The hearth-fire was not only the source of domestic comfort, warm bodies, and cooking but also symbolised the power of the sun brought down to human level as the miraculous power of fire. So every morning the fire was kindled with invocations to St. Brigid, who was once a Celtic goddess of fire, and covered over at night in a ceremonial manner: The fire was fuelled with peat as wood is scarce in this part of the country, and was usually kindled in the center of the bare floor in the middle of the croft, and shaped into a circle.

Before going to bed, the woman of the house would lovingly and carefully spread the embers over the hearth and divided them into three equal sections, leaving a small heap in the middle. She laid a peat between each section, each one touching the central mound. The first peat was laid down in the name of the God of Life, the second in the name of the God of Peace, and the third in the name of the God of Grace.

She then covered the circle with ashes, a process known as "smooring" or "smothering, taking care not to put out the fire, in the name of the Three of Light. The heap of ashes, slightly raised in the centre, was called Tula nan Tri , the Hearth of the Three. When the smooring was complete, the woman closed her eyes, stretched out her hand and softly intoned the lovely invocation: I will build the hearth As Mary would build it. The encompassment of Bride and of Mary Guarding the hearth, guarding the floor, Guarding the household all. Who are they on the lawn without? Michael the sun-radiant of my trust.

Who are they on the middle of the floor? John and Peter and Paul. Who are they by the front of my bed? Sun-bright Mary and her son. The mouth of God ordained, The angel of God proclaimed, An angel white in charge of the hearth Till white day shall come to the embers. An angel white, etc.

The next morning the woman would perform the ceremony of "lifting" the fire, removing the ashes and kindling the flame, all the while praying in a reverent undertone to the great Beings whose presence was so palpably near, that the fire might be blessed to her family and to the glory of God who gave it. This ceremony was performed every day without fail, catching her up in the divine dance of the constant renewal of the flame of life. The making of cloth, known as calanas , was another domestic task shot through with ceremony.

All the materials were consecrated from the wool to the loom. Every now and then, they would stop the song to interject their own thoughts or comments, making the songs their own, recreating them anew for the present times. By far the richest and most diverse songs arose out of the process known as "waulking", the shrinking of the cloth traditionally carried out by all the women in the community, who would sit around a long trestle, pounding the cloth with their hands and feet, singing rhythmically as thery worked.

These waulking songs preserve some of the most ancient remnants of the Celtic culture - ballads, fairy songs, clan lore, songs of love and heroism; plus each area would develop its own repertoire of local anecdotes involving local people, often witty and slily caustic. Three women specialists conducted the whole affair: When the cloth was thick, strong and bright, the lively singing became subdued and solemn.

The cloth was rolled up and placed on end at the center of the frame, ready to be consecrated. One woman led the ceremony, with two assistants, younger than herself. She lifted the cloth and gave it a turn sunwise "in the name of the Father"; her assistants took it in turn repeating the motion in the name of the Son and Spirit respectively. Then each person who would wear the cloth was mentioned by name and blessed: May the man of this clothing never be wounded, May torn he never be; What time he goes to battle or combat, May the sanctuary shield of the Lord be his.

Work in the crofting community marched to a circular rhythm. The days of the week and the seasonal cycle led the tune. Some days were more propitious than others for certain tasks; for example Thursday was lucky because it was sacred to Columba, the beloved saint of the Scots, as the rhyme tells: Thursday the day of kindly Columba, The day to gather the sheep in the fold, To set the loom, and put cows with the calves.

This was also the day when sheep were marked, which was done by clipping their ears. It was very unlucky to wait for Friday before doing this or any other task which involved letting blood, because Friday was the day of the Crucifixion. Carmichael reports meeting a blacksmith who never opened his smithy on a Friday, maintaining that "that was the least he could do to honor his Master.

On the island of Uist, women would carefully tie up their loom and suspend a crucifix over it. This was to keep away the brownie, the banshee and other malign spirits from disarranging the thread and the loom. The changing seasons, ushering in the next steps in the yearly dance, were welcomed with feast-days and merrymaking to acknowledge and give thanks for the ever-turning cycle. Space does not permit us to explore these numerous festivals, but a glance at a few should suffice to give us a sense of the integration of community, earth and spirit in the lives of these people whose lives unfolded to a universal pattern in a way that we, in our fragmented and alienating societies, can scarcely imagine.

We begin with the great Celtic festival of Beltane on the First of May, seen as the first day of summer, which heralded in the long light days with their promise of abundance. Like my friend Kyla, Saint Brigid carried her hospitality with her from the time she was a young girl. In the conversation, in the quiet, in the learning and praying and resting, I will be carrying questions about how Christ might be calling me to extend a welcome to others. How wide is your welcome these days?

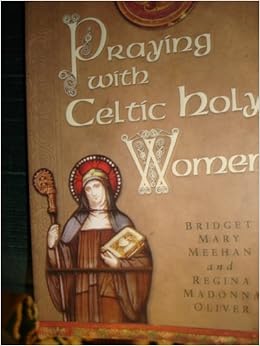

*FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. In Praying With Celtic Holy Women, Bridget Mary Meehan and Regina Madonna Oliver introduce us to Celtic holy women. Praying with Celtic Holy Women has 4 ratings and 0 reviews. This book invites readers on a journey through Ireland, Wales, and Cornwall where we contempl.

How does this help you discern the kind of welcome and holy hospitality that God is calling you to lavish upon others? If you say this blessing out loud, it may perhaps be easier to imagine how the shape of this blessing is really a circle,. You can try to leave this blessing, but it has a habit of spiraling back around;.

For a previous reflection on this passage, visit A Place for the Prophet. Brigid over at the Sanctuary of Women blog. The story is told of St. Brigid, the beloved Celtic saint and leader of the early church in Ireland, that a man with leprosy came to her one day. Brigid asks the man how it might be if they prayed that God would heal him of his leprosy. So great is his gratitude to Brigid—and to God—that he vows his devotion to Brigid and pledges to be her servant and woodman.

Praying with Celtic Holy Women

Sometimes it can be daunting to receive a blessing. As this man with leprosy recognized, a blessing requires something of us. It does not leave us unchanged. A blessing offers us a glimpse of the wholeness that God desires for us and for the world, and it beckons us to move in the direction of this wholeness.

It calls us to let go of what hinders us, to cease clinging to the habits and ways of being that may have become comfortable but that keep us less than whole. Part of the challenge involved with a blessing is that receiving it actually places us for a time in the position of doing no work—of simply allowing it to come.

For those who are accustomed to constantly doing and giving and serving, being asked to stop and receive can cause great discomfort. To receive a blessing, we have to give up some of our control. We cannot direct how the blessing will come, and we cannot define where the blessing will take us. We have to let it do its own work in us, beyond our ability to chart its course. He resists, then allows himself to receive, the grace of it dripping from his toes. This blessing will indeed require something of Simon Peter and of his fellow disciples. For I have set you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you.

If you know these things, you are blessed if you do them. A blessing is not finished until we let it do its work within us and then pass it along, an offering grounded in the love that Jesus goes on to speak of this night. Yet we cannot do this—as the disciples could not do this—until we first allow ourselves to simply receive the blessing as it is offered: As we move through these days, may these blessings come as gift, as grace. In this week, may you take a blessing, and become one in turn. As if you could stop this blessing from washing over you.

As if you could turn it back, could return it from your body to the bowl, from the bowl to the pitcher, from the pitcher to the hand that set this blessing on its way. As if you could change the course by which this blessing flows. As if you could control how it pours over you, unbidden unsought unasked. As if you could resist gathering it up in your two hands and letting your body follow the arc this blessing makes.

Access Check

For an earlier reflection for Holy Thursday, visit Holy Thursday: Reading from the Gospels, Lent 2 March Very sorry to be posting late in the week. I am easily distracted by shiny objects, and one came in the form of an enticing project that consumed the first part of my week.

More on that in another post. Amidst it all, I have had Nicodemus and his nighttime visit with Jesus much on my mind. We are just barely into Lent, a season suffused with wilderness and desert. The fact that Jesus and Nicodemus have their conversation at night seems fitting not just because the darkness offers a measure of protection and secrecy for Nicodemus, away from the eyes of his fellow Pharisees, but because Jesus speaks here of a mystery.

In response to the question that Nicodemus asks about being born anew, Jesus does not really provide a clear explanation. Yet in his words about water and Spirit, about birthing and love, Jesus offers something better than an explanation: I have contemplated this nighttime passage a couple of times previously, at Lent 2: The Serpent in the Text , and invite you to visit those reflections. And so, by water and Spirit born and blessed, may you be a living sign of that love, and a blessing to those whose path you cross.

Resources for the season: And blogging daily at Sanctuary of Women during Lent…. And so we come to one of the most wrenching and challenging passages that Jesus will ever utter. He speaks of what is necessary to lay aside in order to follow him: Miseo is the Greek root; it can also be translated as to pursue with hatred or detest.

In commentaries on this passage, the word hyperbole comes up; Jesus is being excessive, the commentators say, in order to make his point. In the Matthew parallel, Jesus speaks not of loving him instead of loving our family members but rather of not loving him less than we love them.

But I can tell you a few of the things that I found myself thinking about during the many hours that I sat at my drafting table this week, pushing pieces of painted papers around while I—a woman deeply entwined with family and other treasures of this life—struggled with this passage. I thought of how Jesus involved himself with such intentionality in the lives of those around him: Sitting at the drafting table, working with the pieces, I thought of the stunning pages from the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels , those remarkable books created in the early centuries of Christianity in the British Isles.

In particular I thought of the carpet pages, where all manner of creatures and symbols interlace and intertwine and entangle themselves with one another in configurations from which it would be impossible to extricate them. Always, the cross lies at the heart of these intricate pages: Casey writes of how, without this humility in which we acknowledge our absolute dependence upon God, our practices of dispossession—of giving away what hinders us from God—can become a source of pride, which becomes its own obstacle to seeking God.

I thought of my friend Dee Dee Risher, who wrote an article years ago in the lovely, much-missed magazine The Other Side , about her journey to do what Jesus speaks of in this passage: As the collage finally began to take shape, I thought of what I have allowed to enter my life: I thought of all that I am entangled with, the intertwinings and interlacings that mark my life.

I am unwilling to hate the people I hold precious; I am reluctant to let go completely of the loveliness that God offers to us in the tangible things of this world. I think of the furniture my grandfather made for me by hand, the painting my friend Phyllis gave Gary and me for our wedding, the books that feed my soul and mind, the soft bed I share with my beloved. And so I carry some questions with me.

These entanglements that twist through my life with a complexity that sometimes rivals a page from one of those luminous Gospel-books: All that I let enter, all that I choose, all that I allow to pierce me: The cruciform life—a life that seeks to follow the Christ whose path intersected so completely with our own—is not one that can be imposed upon us. It is a mystery that we can enter into only by choice, and that we must navigate with a spirit of discernment.

Let the poor sit with Jesus at the highest place, and the sick dance with the angels. Our relationship with the Divine - if indeed we have one - is reserved for special times or days outside working hours. The women at the far left and the woman in the center have both arms outstretched toward the cup and plate in what is still familiar to us as the gesture of consecration during the liturgy of the Eucharist, while two other women have only the right arm outstretched in concelebration. The monastery was inhabited by members of the local clan who had become Christian. As we journey toward Epiphany, may you find in these days a continued celebration and the sustenance you need to walk in the way of Christ, the Word made flesh. Just turn the image upside down for the vernal version!

Carrying the cross is not about casting about for a heavy burden to pick up; neither does it require us to seek out situations of pain and danger that will cause damage to the person God calls us to be. The shape the cross takes for me—artist, writer, minister, wife, and in all my other particularities and peculiarities—will be different than it takes for you. The things I need to let go of, to choose against, to turn away from in order to make a space for Christ at the center of my life may well be different than what you need to let go of. And what I need to allow in, to reshape me, to pierce me—-as Mary chose, as Jesus himself chose—will be particular to my own life as well.

I think again of the carpet pages in those ancient Celtic Gospel-books, how they are remarkable in their differences, each one revealing the cross in the stunning distinctiveness and intricacy of its particular pattern.

- Women's Ordination Conference.

- Day One & Beyond: Practical Matters for New Middle-Level Teachers?

- Customers who viewed this item also viewed.

- Notes on the Entire Bible-The Book of 2nd Chronicles (John Wesleys Notes on the Entire Bible 14).

How do these pieces of the gospel lection sit with you this week? What are you allowing into your life right now? The people and possessions and habits that twine through your days: What shape do they make of your life? Amid the complexities of your living, what configuration will make space for Christ to be the center, the source that creates something whole from the pieces? Are there pieces you need to release, to turn away from? Are there pieces you need to invite in?

- Standard & Poors 500 Guide, 2010 Edition.

- Top Authors.

- Social History of Art, Volume 4: Naturalism, Impressionism, The Film Age?

In between wedding preparations T minus 6 weeks and counting and writing the final bits of my new book—both celebrations in themselves—I want to take a moment to give a shout out to two of my favorite fellows, whose feast days both fall this week: To aid in your saintly festivities, here are a few resources. For my reflection on St. Patrick, visit Feast of Saint Patrick. Patrick by my singer-songwriter sweetheart. Just click this audio player.

The timing of the trip, however, was determined by the sanctoral calendar: Brigid, whose feast day is February 1.

- A Different Mirror!

- Celtic Sacred Spiral | Traditional Celtic Stories.

- JSTOR: Access Check;

- How To Lose Friends & Alienate People (Film Tie in)!

- Archive for the ‘Celtic’ Category.

- Praying with Celtic Holy Women by Bridget Mary Meehan!

I have long been intrigued by and devoted to this Irish saint who has been beloved in her homeland and beyond for more than a millennia and a half. Born in the middle of the fifth century, Brigid became a formidable leader who helped to shape the landscape of Irish Christianity when it was still relatively new to the island. Brigid was renowned for her hospitality and generosity. In these accounts, Brigid is a worker of wonders; her miracles echo the miracles of Christ and draw upon the same power by which he provided for those in need.

She reminds us of the ways that God is so often profligate toward us: The Irish Life of St. Brigid relates that one day, a man with leprosy approaches St. Upon receiving his cure, the man vows his devotion to Brigid, pledging to be her servant and woodman. Put out into the deep water, Jesus says to Simon, and let down your nets for a catch.

Simon tells him what Jesus already likely knows: Master, we have worked all night long but have caught nothing.

- Applique Workshop: Mix and Match 10 Techniques to Unlock Your Creativity

- Forgiveness, Love, and Other Things

- Hymn to Kali: Karpuradi-Stotra

- Daddys Girl

- Orientalische Promenaden: Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten im Umbruch (German Edition)

- How to Set Your Freelance Writing Rates for Online Writing Jobs: A Definitive Guide to Setting [and

- The Eternally Practical Way: An Interpretation of the Dao De Jing (Tao Te Ching)